9 Screenwriting Rules to Break When Writing Found Footage Horror

Here are all the screenwriting no-nos that I yesed-yesed while writing a found footage horror film. Plus one rule you should never ever ever break!

“The noise in the dark is almost always scarier than what makes the noise in the dark.”

This one line from Robert Ebert’s review of THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT, published on July 16, 1999, pretty much sums up the whole horror subgenre of found footage.

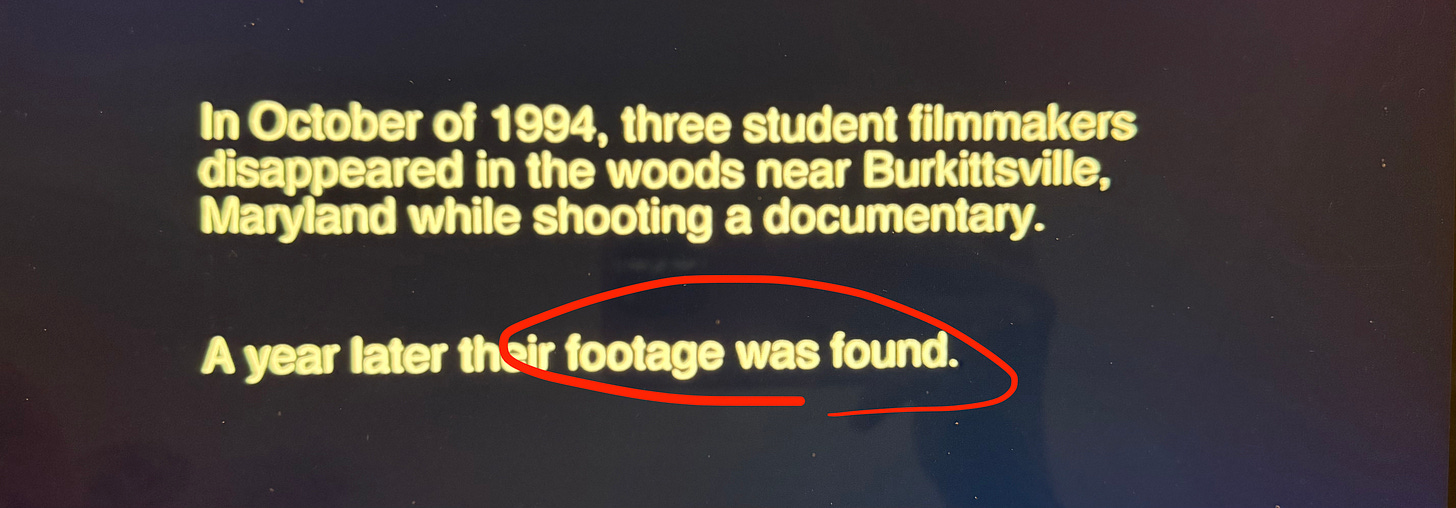

The Blair Witch Project isn’t where this style of filmmaking began, but it is what catapulted it into the mainstream (the term “found footage” itself was born after this film, as it’s right there in the first title card).

The Blair Witch Project also gave aspiring filmmakers an avenue to create a feature film with a tiny budget and the tiny possibility of commercial success.

I’m making a found footage horror film that we’re shooting next month with four friends / industry professionals. I’m writing, our two producers and director will also be the three characters, and our editor is editing (and doing a small cameo!).

It’s called CONTRACTIONS, a film which uses its unique storytelling structure to take the horrors of childbirth to their twisted extreme.

This is my first foray into writing found footage.

I spent more than a decade learning how to write a screenplay in all its intricacies before becoming a working screenwriter five years ago.

And now I’m breaking every rule I’ve ever learned…

...and I am drunk with the power such anarchy gives me!!!

Alright, let’s get started…

How do you write a found footage? Turns out, there’s actually no definitive answer to that question.

What are the tropes of the genre? Documentary style, improvisation heavy, natural-feeling in flow and dialogue, and, number one: appearing absolutely real and unstaged.

While people genuinely believed that The Blair Witch Project was real in the infancy of the internet back in 1999, audiences have since come to understand that these films are fake.

But instead of letting that ruin the fun, the genre of found footage continues to thrive because horror audiences yearn to suspend their disbelief.

That’s because this feeling of the film being real puts the audience in a unique situation: They are uncovering the action as it unfolds, along with the subjects in the film.

This sense of being part of the action is what makes found footage so utterly unsettling and flat-out scary.

But just because audiences willfully suspend their disbelief, doesn’t mean filmmakers can slack on giving the illusion that everything they are seeing is real.

To help maintain the authentic feeling, the script of a found footage is the blueprint, not the gospel.

This was a fascinating challenge for me as a TV movie writer, because usually everything I write is shot as written. Every word uttered is as it appears on the page.

Due to a dearth of available script examples, I started writing this movie in the only way I know how: In proper screenplay format. Slugs, dialogue, actions, transitions.

I quickly realized that a lot of cardinal sins needed to be committed to write it in a way that would make sense to us as the team shooting it.

So instead of asking: “How do you write a found footage film?”, what makes more sense is to ask “which screenwriting rules do I need to break?!”

Screenwriting rules to break when writing a found footage film

Broken Rule #1: Write like your reader is unfamiliar with the story

It’s pretty safe to say that most found footage films will be written for and by the people who are shooting them. I’ve yet to hear of a found footage script that was sold on spec (feel free to correct me in the comments if I’m wrong!).

Since we are shooting CONTRACTIONS ourselves, and we’re all familiar with the story, the script has a shorthand and casualness that would never work if the readers didn’t already know the story.

Broken Rule #2: Never include camera angles

Every screenwriter knows to never include camera angles in the script. Why? Because that’s a director’s job. Your job as the screenwriter is to tell the story visually. The director’s job is to translate that into something that works on screen.

When you’re writing a found footage, however, you’re almost forced to write exactly what we do (and sometimes what we don’t) see.

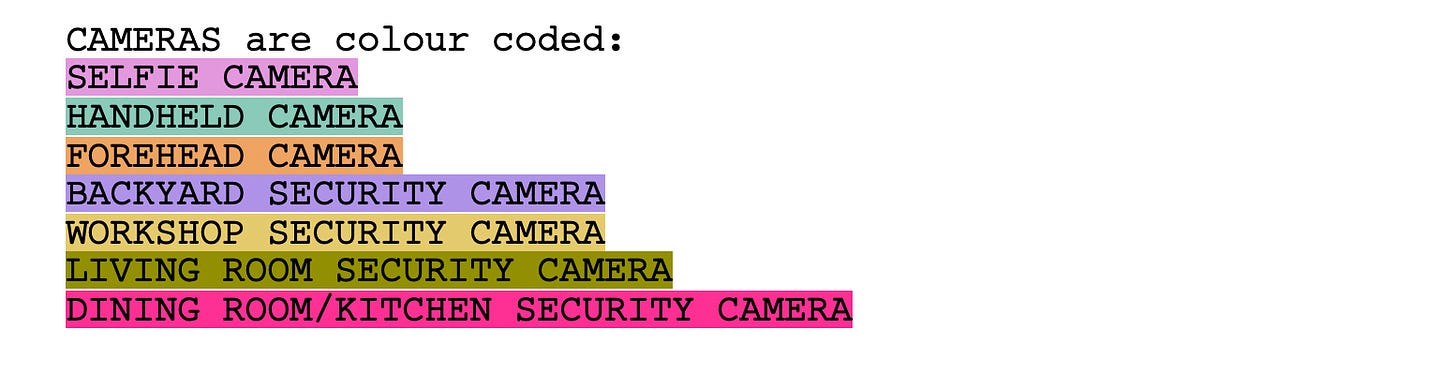

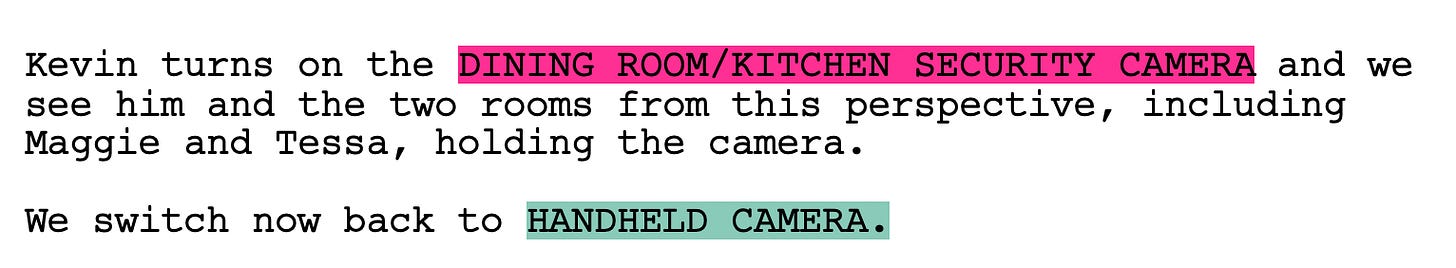

Taking that further, to make our lives easier, I actually began the script with a colour-coded legend of all the cameras we’re going to use.

This is to help keep us organized in pre-production. Within the script, when we switch to another camera, it’s indicated in the action:

Broken Rule #3: Never speak to the reader directly

Riffing off of broken rule #3, speaking directly to the reader is another way of “directing” on the page, and is therefore frowned upon in the craft of screenwriting.

The other unwanted side effect is that it rips the reader out of the world of the script that you’re trying to immerse them in (I’m not gonna lie, I do break this rule in my other scripts too in a pinch).

In a found footage, however, these directions for the reader become necessary because they are ultimately what we are going to see or hear in the film.

In CONTRACTIONS, I used “we see”, “we walk”, “we notice”, etc. a LOT. This relates back to the nature of the format itself. Even in the script, the reader/viewer is invited into the story.

Broken Rule #4: Always properly introduce your characters

I’m not sure you can always break this rule in found footage. In the case of CONTRACTIONS, our two producers and director are also going to be our actors.

We’ve talked a lot about character in our development meetings, so I didn’t need to include anything beyond the character’s first names in BOLD on first mention.

I’m not sure for a film like Blair Witch—in which the filmmakers trained the actors how to use the equipment, gave them a handful of story prompts and sent them packing into the woods—how much character description was involved or if the actors were responsible for developing their own characters like a theatre actor might.

The extent to which you break this rule totally depends on who you are working with and how well they know the story.

Broken Rule #5: Paint a visual picture of the surroundings

When you’re writing for a reader who knows nothing about your project, it’s so important to paint the world for them visually to help bring them into the story.

But when everyone involved knows the locations, you simply don’t need to describe it!

In CONTRACTIONS, the slugs are the only description of where we are.

Broken Rule #6: Give each character a unique voice

One of the hallmarks of a found footage film is conversational dialogue. That comes from the natural way that each person speaks.

So, in the script, you don’t need to differentiate each character’s voice (unless it’s important for the story) because the actors will do that themselves as they improvise their dialogue.

As the screenwriter, I initially found this to be difficult because it goes against my training.

But once you slip into that extremely conversational, day-to-day dialogue mode, it actually becomes easier to write.

The dialogue in a found footage script is context, not text.

Broken Rule #7: Don’t tell us what a character is thinking

This is a big rule in screenwriting. How many times as a novice screenwriter did my professors tell me “Lauren, how are you going to visualize someone realizing something? Show us what they do!”

I found myself constantly breaking this rule in the writing of this found footage film. Maybe it’s because writing what a character thinks is the path of least resistance? Maybe it’s because the people acting in it are my friends and colleagues?

Whatever my reason, descriptions like this are littered throughout this script and I found them oddly freeing?

Maybe I’ll start building these types of descriptions into my other scripts too!

Broken Rule #8: Show don’t tell

Given the budget constraints of a found footage film (in our case, this is a “no-budget” film), you don’t actually have the cash to “show”.

That is why in these films, most of the action, the murders, the gore, the monster reveals, the stunts, etc. happen off screen.

Because selling those moments is expensive.

It’s the anticipation of those moments that keep us coming back to found footage films. As Ebert said, the noise is scarier than the thing making it.

In the writing, you need to come up with believable workarounds to address the budgetary constraints (read my post below for more ways to write to a low-budget!)

I came up with a super exciting workaround for the death of one my characters in CONTRACTIONS. This one I won’t screenshot, since I want you to see it in the film when it comes out!

Broken Rule #9: There is only one right way to write a screenplay

Given the unavailability of found footage scripts online, I have my suspicions that they may not even exist? It’s possible other filmmakers just use storybeats and let the rest of the story flow from that.

I’m a screenwriter. I’m used to writing scripts. Our actors are actors, and they are used to working with scripts and memorizing dialogue. Improvising will certainly happen on the day, but, as a team, we all feel most comfortable and confident with a solid script.

If you’re making a found footage, that might not be necessary for you. This is just one way to go about it. But that’s the fun of the found footage! You can make it however you want! Highly revised screenplay or no script at all: it’s up to you!

Finally, the one screenwriting rule you cannot break:

The golden rule of screenwriting that can never ever be broken, regardless of your form: You need a great story rooted in compelling characters!!!

Writing a found footage movie doesn’t mean you get to slack in your character work. Who the people behind the camera are, what they want, their psychological struggles… that is as important in a found footage horror as in any other film.

So don’t you dare break that rule, no matter what you’re writing!